Title: Sciame di Dirigibili (Zeppelin Swarm)

Year: 2009

Dimensions: Variable

Technique: Stuck zeppelin ‘“ publicity campaign ‘“ photomontage ‘“ souvenirs ‘“ street artists ‘“ printed and digital media ‘“ indoor exhibition

Exhibition: Making Worlds ‘“ 53 International Art Exhibition ‘“ Venice Biennial

Place: Venice ‘“ Italy

Hector Zamora’™s work resides in between familiar spaces. Between sculpture and architecture, between conceptual and formal, between real and imaginary, between public and private. The slippage between these known categories makes us uneasy, yet it is exhilarating to find something growing there, in the crack in the sidewalk, where we had thought nothing could survive.

Two of Zamora’™s previous works, Paracaidista, 2003-2004, and Specular Reflexions, 2007, explore these in-between spaces by exploiting the exhibition space itself as an object of scrutiny. This exploitation is more explicit in the first project, Paracaidista, in which Zamora built an annex surrounding the outside of the second-floor exhibition space of the Museo Carrillo Gil in Mexico City. The artist himself lived in the 75-square-meter space for three months, using water and electricity sapped from the museum. In this work the private space literally adheres, parasitic, to the public institution, the artist a sucker fish on the shark of the museum. The exploitation is not quite so one-sided, however; the museum surely benefits from the relationship. Is such a symbiosis really possible?

In the less-intimate intervention of Specular Reflexions, a two-way mirror film was applied to both sides of all 16 windows of the Fayman Gallery at the Museum of Contemporary Art in San Diego. The mirrored windows effectively reverse the viewer’™s gaze, both inside and outside the gallery, suggesting a lack of institutional transparency. Reflexions begs consideration of the way in which the museum space defines itself as such, and, as in Paracaidista, asks how the museum situates itself in relation to the public and private realms.

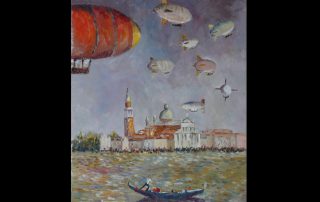

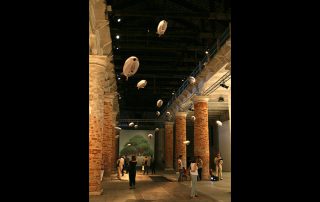

Zamora’™s work at the Venice Bienale is quite literally stuck in between two walls. A life-sized zeppelin is caught adrift, far from its fleet, between the two walls that form the Arsenale corridor. Neither an explicit part of the exhibition or an entirely distant one, the zeppelin creates and inhabits a place entirely its own. Furthermore, the zeppelin is stuck not only in space, but seems to be somewhat adrift in time, perhaps harkening from the days when the festival di dirigibili, the flying machine festival, was a common occurrence in Venice. The project, titled Zeppelin Swarm, which includes a massive campaign to publicize a zeppelin fair that never really occurred, investigates the ways in which history is constructed in the public imagination via use of public space. From the participation of Venetian street artists to the implantation of viral media on the internet, Zamora has ensured that the imaginary zeppelin fair, as well as the real zeppelin, will occupy a place in Venice’™s history. Yet this position is a tenuous one: how to locate within history an event that never happened?

Due to the extremely site-specific nature of the piece, a strong connection is forged between history and place. And this connection takes on a political nature. Establishing a false history is generally driven by a political need to structure time and belief. Even when this need is absent, the structuring of history retains political connotations. And so, even in the absence of any overtly political claim, the formal structure of Zamora’™s piece forces one to consider it a political action.

It may seem that the very notion of a history without physical origin is more a Baudelairian concept than a post-modern one ‘“ and perhaps a certain nostalgia for modernist thought is what that the piece is meant to evoke. Yet the physical artifact of the zeppelin problematizes the notion of the entirely imaginary history. We are given a physical fragment of the occurrence, and we become unsure where one reality stops and another begins. In the information world, history is accessible and alterable by anyone. The subjective nature of all types of information has never been so clear, and it becomes harder and harder for one person to own the facts. History itself belongs to no one; it floats above the ground, unnoticed, until occasionally it gets stuck in some corridor and we are forced to consider it.

In many ways, Sciame di Dirigibili references the work of Panamarenko. Like most of Panamarenko’™s work, Zamora’™s project relies heavily on the audience’™s imagination. However, it differs from Panamarenko’™s flying machines in the way that it incorporates its context’”in an immediate sense and also in the grander sense of the city as a whole’”and therefore stakes an undeniably political claim. After all, Zeppelin Swarm as project is much, much more than the physical artifact; the entire universe in which the zeppelin exists has been fabricated as well. If Panamarenko’™s machines invoke the forward-looking powers of imagination, the stuck zeppelin project in its entirety is more of a backward glance, a temporary halting of time’™s inevitable trajectory. Further, and in keeping with Panamarenko’™s spirit, the Zeppelin Swarm is an experiment. It tests the ability of the imagination to fly.

Elvia Pyburn-Wilk